Ancestry, Genealogy, Ethnicity - Let's Talk Terminology

Having an understanding of the definition of a word is the basis of understanding what someone is saying. The terminology needs to be understood in the same way by the person using it and the person reading or hearing it. I answer lineage research questions from a lot of people who seem to not understand what is meant by some terms, and others who conflate or confuse others. It’s not their fault! If it’s never been explained, it’s likely that a meaning from some other field or aspect has made its way into their understanding. So let’s talk terminology in the context of lineage research.

Firstly, what do I mean by lineage research? I mean research into the biological connection and social relationships that extend from a person through the parents, and their parents, and their parents, and so on (i.e., a family tree). This is also called genealogy.

Genetic genealogy is the use of DNA to find familial, or cultural/ethnic, relationships.

The first person in the family tree, or proband as used in medicine and genetics, is the point of reference or starting point. So all relationships depend on who this starting point is and are named based on their relative association with the other members of the tree. For example, your great-grandfather is your father’s grandfather but your son’s 2x great-grandfather.

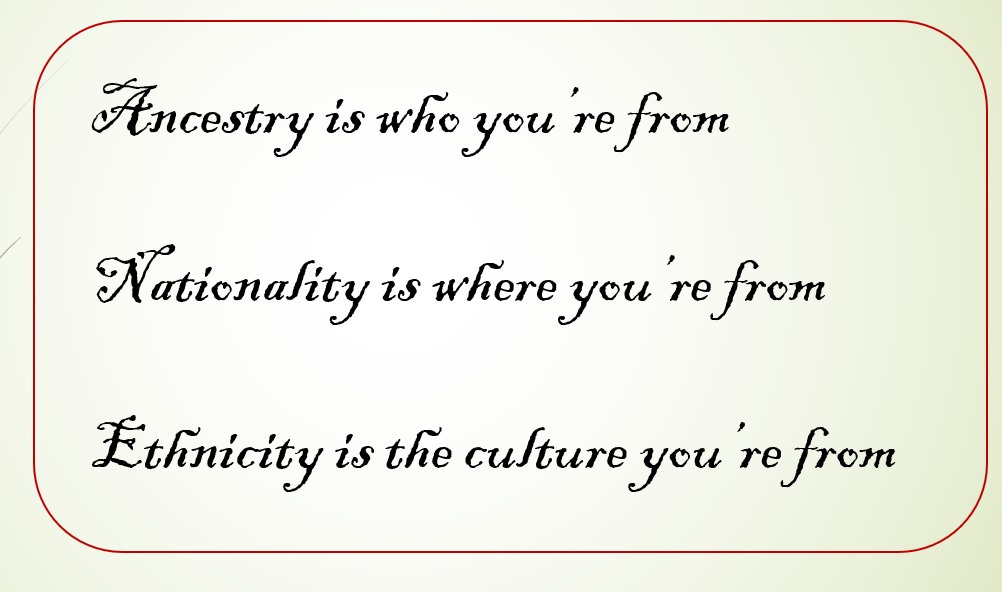

The people directly above the proband in a family tree are ancestors, and their general status (geography, religion, nationality, etc) is the proband’s ancestry. In contrast, the people directly extending below someone in a tree (i.e., born later, such as children and grandchildren) are descendents. These are direct relationships.

Ethnicity is a cultural association. It’s a population subgroup (geographic or otherwise) that a family may belong to or have belonged to at some point in time. From the dictionary:

the quality or fact of belonging to a population group or subgroup made up of people who share a common cultural background or descent.

Ethnicity estimates from DNA testing compare your results to current geographic or cultural populations to show potential ancestry, but the populations in those areas may have changed since your ancestors lived there. Also, this shouldn’t be confused with nationality, which is the country that you or your ancestor called home.

Here’s a good site for how to reference different nationalities and populations.

If I was asked, “why doesn’t my Irish grandmother show up in my DNA results - there’s no Irish in my ethnicity estimate? There’s lots of German instead.” I’d ask in return, was your grandmother Irish in culture or simply lived there? If she came from Germany, then her family was likely German and that’s what shows in the DNA (or she married a non-Irish and not enough of her Irish DNA passed to you by chance - you’d only share an expected average of 25% of markers with her and no telling how much of her DNA was “Irish”).

In genealogy, the nationality is important because it tells you where to look for records. But in genetic genealogy, it won’t show up. This can get confusing for ethnic populations that refer to their “nations”, such as Native Americans, but this is just a different use of the terminology in place of “tribe” or “clan”. Once you understand how the term is used in a particular context, you can translate it into what information is and isn’t provided.

When looking at genetic genealogy, things can also get confusing when your ancestors were part of a diaspora. The National Geographic has a much better primer on this than I can provide. In my own case, my German ancestors were actually several generations of Russians (i.e., Volga Germans). Americans often tend to have a connection to one diaspora or another, as do the British. This is why I always urge caution in expecting clear results from ethnicity estimates.